On this page, we outline ways you can eat greener, by thinking about where your food originates, eating locally-produced seasonal products, and taking measures to reduce food waste.

Impacts of food production

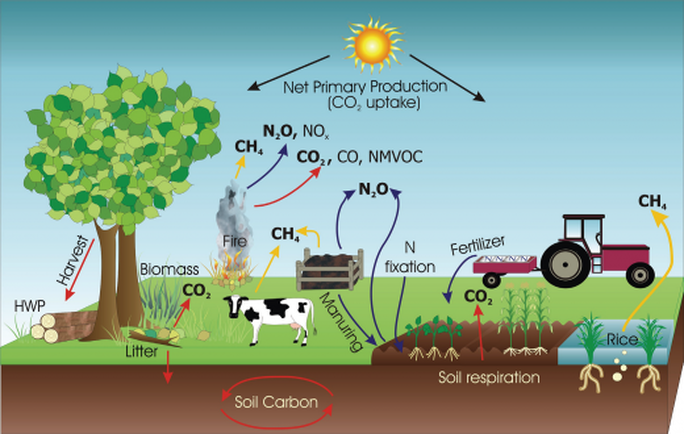

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change's Special Report on Climate Change and Land (2019) estimates that agriculture is directly responsible for up to 8.5% of global greenhouse gas emissions, with a further 14.5% coming from land use change (mainly deforestation in the Global South to clear land for food production). In the UK, direct emissions from agriculture and horticulture account for about 10% of our total greenhouse gas emissions. The main greenhouse gas emitted by agriculture is methane (from ruminants including cattle and sheep), followed by nitrous oxide (from fertilisers) and carbon dioxide (predominantly from energy and fuel). Food processing and transportation generate further emissions.

The climate change impacts of our diet are complex. If you want to read a balanced, evidence-based account of the links between global food production and climate change, have a look at the interactive guide by Carbon Brief. Do, however, bear in mind that comparisons of the carbon footprints of different foodstuffs in this guide are based on global production figures – these do not automatically translate to a UK context where farming methods are generally less intensive. For a UK perspective, the Agri-climate report 2021 produced by DEFRA is an excellent source of information about emissions from UK agriculture and changing trends over time.

The overall message of this page is to eat what you enjoy but think carefully about where your food comes from and how it is produced – buy local and seasonal products wherever you can – and whatever you eat, try to avoid waste.

The climate change impacts of our diet are complex. If you want to read a balanced, evidence-based account of the links between global food production and climate change, have a look at the interactive guide by Carbon Brief. Do, however, bear in mind that comparisons of the carbon footprints of different foodstuffs in this guide are based on global production figures – these do not automatically translate to a UK context where farming methods are generally less intensive. For a UK perspective, the Agri-climate report 2021 produced by DEFRA is an excellent source of information about emissions from UK agriculture and changing trends over time.

The overall message of this page is to eat what you enjoy but think carefully about where your food comes from and how it is produced – buy local and seasonal products wherever you can – and whatever you eat, try to avoid waste.

|

The main greenhouse gas emission sources, removals and processes in managed ecosystems (Source: Climate Policy Info Hub).

|

Think about where your food comes from

Food miles

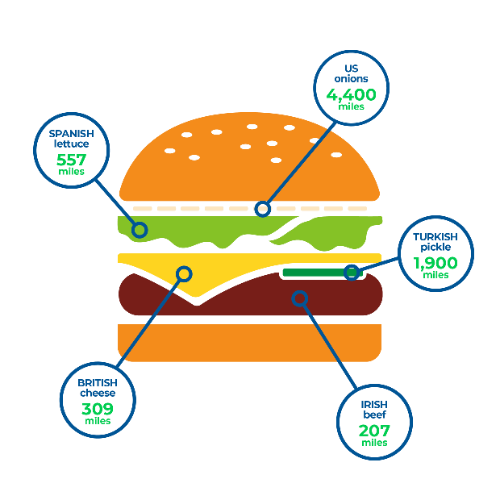

The food you eat is a personal choice. If you want to eat greener, one of the first things to think about is how far your food has travelled to get to your kitchen. That journey – the distance from farm to plate – is what we mean by the term ‘food miles’. Whether you are a meat-eater, vegetarian or vegan, if your ingredients have come a long way, especially by air, they are likely to have a large carbon footprint. Flying in food creates up to 10 times more carbon emissions than road transport and up to 50 times more than shipping.

There are some useful online tools that can help you estimate the food miles of specific ingredients. However, unless you are buying products grown or reared by a local supplier, it’s almost impossible to know exactly how far your food has travelled. UK law requires meat, fish and seafood labels to show their country of origin but that doesn’t tell you how the food was transported or where else it’s been. In our globalised world, food may be grown in one country, then processed and packaged in another, before it reaches your local store. A simple shop-bought mixed fruit salad, for example, represents a food miles world tour that would make Ed Sheeran blush.

When adding up food miles you also need to consider your journey to and from the shop. If you travelled by car, bus or taxi, these create additional carbon emissions (even if the vehicle was electric). Yes, those trips to Asda, Tesco and Waitrose in Hailsham soon add up in terms of emissions. If you have your weekly shop delivered, the distance it covers from the warehouse to your home is also critical.

The food you eat is a personal choice. If you want to eat greener, one of the first things to think about is how far your food has travelled to get to your kitchen. That journey – the distance from farm to plate – is what we mean by the term ‘food miles’. Whether you are a meat-eater, vegetarian or vegan, if your ingredients have come a long way, especially by air, they are likely to have a large carbon footprint. Flying in food creates up to 10 times more carbon emissions than road transport and up to 50 times more than shipping.

There are some useful online tools that can help you estimate the food miles of specific ingredients. However, unless you are buying products grown or reared by a local supplier, it’s almost impossible to know exactly how far your food has travelled. UK law requires meat, fish and seafood labels to show their country of origin but that doesn’t tell you how the food was transported or where else it’s been. In our globalised world, food may be grown in one country, then processed and packaged in another, before it reaches your local store. A simple shop-bought mixed fruit salad, for example, represents a food miles world tour that would make Ed Sheeran blush.

When adding up food miles you also need to consider your journey to and from the shop. If you travelled by car, bus or taxi, these create additional carbon emissions (even if the vehicle was electric). Yes, those trips to Asda, Tesco and Waitrose in Hailsham soon add up in terms of emissions. If you have your weekly shop delivered, the distance it covers from the warehouse to your home is also critical.

|

The ingredients for your burger could have travelled the equivalent of 8,000 miles before you eat it (Image source: Food Miles).

|

More than miles

As conscious consumers, we are doing the world a favour if we reduce the food miles associated with our meals. However, food miles only tell you one thing – distance. It turns out that (other than for foods that are moved via air), transport contributes a relatively small proportion of the total emissions compared to other inputs.

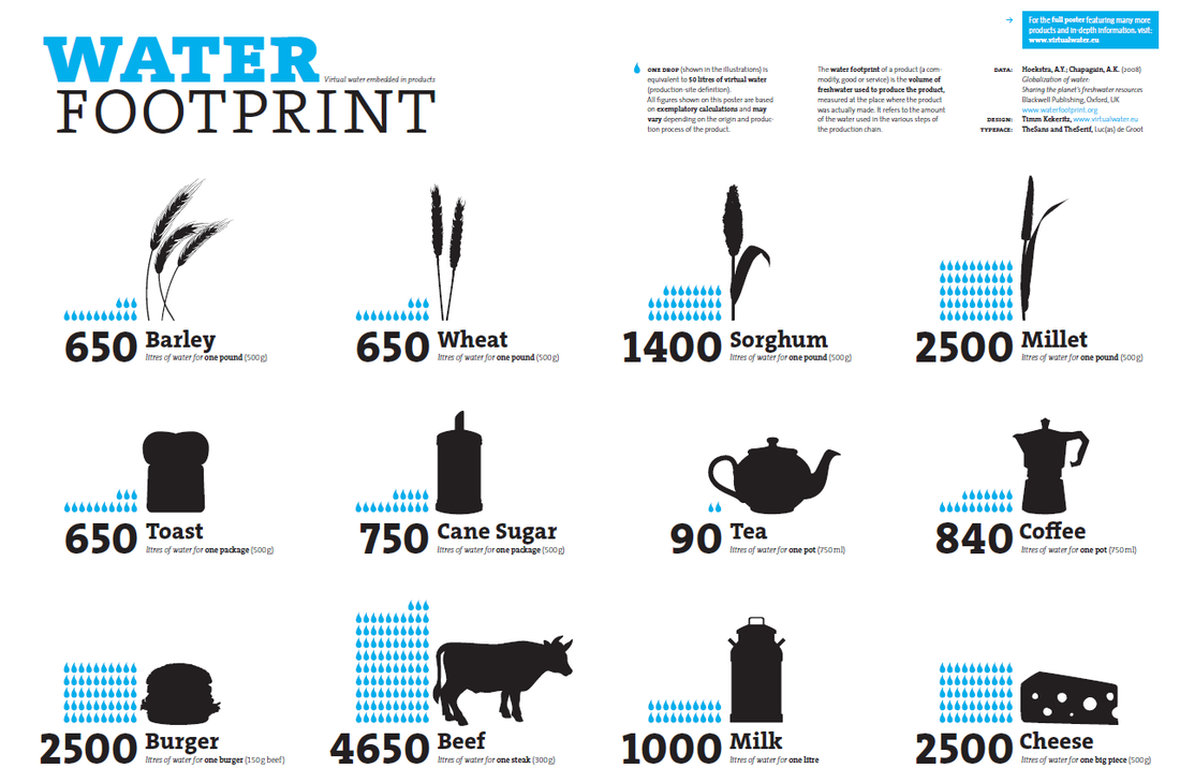

Many foodstuffs have a large water footprint – that is, they require substantial volumes of fresh water to produce a given mass or volume of product. Some of this water is termed “green water” – essentially, the rainwater used to grow most fruits, vegetables, grass, forage and feed crops. However, some food production also relies on “blue water” – water that is abstracted from rivers or groundwater, or taken from the mains water supply, and used for irrigation, as drinking water for poultry and livestock, and for washing, cleaning and feed processing.

The humble glass of milk is a good illustration of the complex water footprints of everyday food. Based on global figures, a 200 ml glass of cow’s milk requires, on average, 120 litres of water to produce (the equivalent of two 8-minute-long showers). The figure is relatively high because, globally, the feed for all but the most sustainably-reared dairy cattle comes from irrigated grain or grass, which has a large water footprint. The water footprint will be lower in more water-efficient dairy farm systems, such as those in the Chiddingly area, that rely predominantly on rain-fed grass for fodder.

If you think you are being environmentally friendly by drinking almond milk rather than dairy, you should think again. Commercial almond trees require irrigation. So, that 200 ml glass of almond milk needed, on average, 80 litres of water input (most of which was blue water), and that water was pumped using electricity. If you want a non-dairy option, you would be better off drinking oat milk, produced from oats grown in the UK using mainly green water. If you want to know more, have a look at the report on ‘The Volumetric Water Consumption of British Milk’ produced by Cranfield University.

As conscious consumers, we are doing the world a favour if we reduce the food miles associated with our meals. However, food miles only tell you one thing – distance. It turns out that (other than for foods that are moved via air), transport contributes a relatively small proportion of the total emissions compared to other inputs.

Many foodstuffs have a large water footprint – that is, they require substantial volumes of fresh water to produce a given mass or volume of product. Some of this water is termed “green water” – essentially, the rainwater used to grow most fruits, vegetables, grass, forage and feed crops. However, some food production also relies on “blue water” – water that is abstracted from rivers or groundwater, or taken from the mains water supply, and used for irrigation, as drinking water for poultry and livestock, and for washing, cleaning and feed processing.

The humble glass of milk is a good illustration of the complex water footprints of everyday food. Based on global figures, a 200 ml glass of cow’s milk requires, on average, 120 litres of water to produce (the equivalent of two 8-minute-long showers). The figure is relatively high because, globally, the feed for all but the most sustainably-reared dairy cattle comes from irrigated grain or grass, which has a large water footprint. The water footprint will be lower in more water-efficient dairy farm systems, such as those in the Chiddingly area, that rely predominantly on rain-fed grass for fodder.

If you think you are being environmentally friendly by drinking almond milk rather than dairy, you should think again. Commercial almond trees require irrigation. So, that 200 ml glass of almond milk needed, on average, 80 litres of water input (most of which was blue water), and that water was pumped using electricity. If you want a non-dairy option, you would be better off drinking oat milk, produced from oats grown in the UK using mainly green water. If you want to know more, have a look at the report on ‘The Volumetric Water Consumption of British Milk’ produced by Cranfield University.

|

The water footprint of everyday food products (graphic: Water Footprint Network; data: Mekonnen & Hoekstra, 2011).

|

There are other hidden carbon emissions associated with our food. Synthetic fertilisers and pesticides require energy to produce, and so have associated carbon emissions. This is why eating organic is generally better for the planet. Some foodstuffs require additonal heat to grow them or refrigerators to preserve them. For example, many commercial greenhouses in the UK are heated to extend the growing season. As a result, tomatoes grown under heated greenhouse conditions may have a higher carbon footprint than tomatoes imported from Spain – even including the extra transport. During our apple season, British apples have a lower carbon footprint than those imported from New Zealand. However, for the rest of the year, imported apples can have a lower carbon footprint due to the energy used to refrigerate British apples.

Shop locally, think seasonally

Why eat local?

In addition to its environmental benefits, eating locally-sourced food helps support the rural economy. There are studies that dispute this, but locally grown seasonal vegetables taste better than mass-produced products from supermarkets. Rather than relying on Tesco or Waitrose, try to buy from a local greengrocer or farm shop – and talk to them about where and how their products are grown. Local allotment holders may also have excess produce to sell.

If you have the space, then nothing beats growing your own – a small garden or even a windowsill can produce a surprising amount of food. If you’re not sure where to start – or simply want some tips and advice – then the Royal Horticultural Society website is a great source of information. Remember though, to minimise the use of artificial pesticides – there are plenty of effective alternatives – and avoid peat-based fertilisers and composts. Peat comes from lowland peat-bogs, some of the most important ecosystems for carbon sequestration on the planet. We are using peat up far quicker than it can be naturally replenished, meaning that these ecosystems can no longer play their role in maintaining the world’s carbon cycle.

In addition to its environmental benefits, eating locally-sourced food helps support the rural economy. There are studies that dispute this, but locally grown seasonal vegetables taste better than mass-produced products from supermarkets. Rather than relying on Tesco or Waitrose, try to buy from a local greengrocer or farm shop – and talk to them about where and how their products are grown. Local allotment holders may also have excess produce to sell.

If you have the space, then nothing beats growing your own – a small garden or even a windowsill can produce a surprising amount of food. If you’re not sure where to start – or simply want some tips and advice – then the Royal Horticultural Society website is a great source of information. Remember though, to minimise the use of artificial pesticides – there are plenty of effective alternatives – and avoid peat-based fertilisers and composts. Peat comes from lowland peat-bogs, some of the most important ecosystems for carbon sequestration on the planet. We are using peat up far quicker than it can be naturally replenished, meaning that these ecosystems can no longer play their role in maintaining the world’s carbon cycle.

Why eat the seasons?

When foods are grown out of season, they are unable to follow their natural growing and ripening cycles. For certain fruits and vegetables to be available year-round, post-harvest treatments are used, including preservation and ripening agents. These include chemicals, gases and heat processes, all requiring additional energy inputs.

Eating with the seasons reduces the energy (and associated carbon emissions) needed for food production and transport. It also means you avoid paying a premium for food that is scarcer or has travelled a long way. Eating seasonally has the additional benefit of allowing you to reconnect with nature's cycles and the passing of time. Seasonal food is also usually fresher and so tends to be tastier and more nutritious.

If you want to know more about eating seasonally, have a look at the Eat Seasonably, Eat the Seasons and Food Savvy websites, where you’ll also find great seasonal recipe ideas.

When foods are grown out of season, they are unable to follow their natural growing and ripening cycles. For certain fruits and vegetables to be available year-round, post-harvest treatments are used, including preservation and ripening agents. These include chemicals, gases and heat processes, all requiring additional energy inputs.

Eating with the seasons reduces the energy (and associated carbon emissions) needed for food production and transport. It also means you avoid paying a premium for food that is scarcer or has travelled a long way. Eating seasonally has the additional benefit of allowing you to reconnect with nature's cycles and the passing of time. Seasonal food is also usually fresher and so tends to be tastier and more nutritious.

If you want to know more about eating seasonally, have a look at the Eat Seasonably, Eat the Seasons and Food Savvy websites, where you’ll also find great seasonal recipe ideas.

What about locally-produced meat?

Arguments about the climate change impacts of animal- versus plant-based diets are many and complex. Meat from livestock has come into particular focus. Cattle release large quantities of methane during their lifetime (a gas that’s more harmful to the planet than carbon dioxide) and it generally takes more resources to produce beef than comparable other food items. However, the scale of the difference between food items – and the emissions associated with meat production compared to other sources of greenhouse gases – vary according to who you read. As this article comparing greenhouse gas emissions from livestock and transport shows, much depends upon whether direct and/or indirect emissions are considered. The use of general figures also masks the fact that agricultural production systems vary widely across the world.

Greenhouse gas emissions associated with UK meat production are significantly lower than the global average. The most comprehensive statistical analysis of global food systems to date (by Poore & Nemecek in the leading academic journal Science), examined emissions, land use, and other impacts of global agriculture using a life cycle assessment. Life cycle figures account for emissions produced along the whole supply chain, including those from land-use change, on-farm activity, feed production, processing, transport, retail and packaging. The results show that beef from UK beef herds had an average emissions intensity of 48.4 kg carbon-dioxide-equivalent per kg retail weight compared to a global average of 99.5 (greenhouse gases are often presented in units of carbon-dioxide-equivalent – this is a common unit of measurement that allows comparisons to be made between emissions of different gases). For beef from UK dairy herds, the figures were 25.9 versus 33.3; for lamb, 37.4 versus 39.7; and for pork, 11.9 versus 12.3.

Data published by the Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board suggest that the average emissions intensity of UK livestock products up to the point they leave the farm gate is even lower. Beef from UK beef and dairy herds had an average emissions intensity of 23.4 kg carbon-dioxide-equivalent per kg carcass weight; lamb 25.2; and pork 4.8. The figure for the most sustainably-reared beef was as low as 5.6 kg carbon-dioxide-equivalent per kg carcass weight.

The over-riding message from these studies is that, if you are going to eat meat, choosing meat from animals that are locally-reared on low-intensively managed farmland is best in terms of reducing the carbon footprint of your diet. Local butchers and farm shops often sell this product and can tell you where the meat originated. If the meat comes from a local farm via a local abattoir, the resulting food miles will be very low. Some of the most sustainable meat production is by local smallholders, many of whom will sell to you directly.

Arguments about the climate change impacts of animal- versus plant-based diets are many and complex. Meat from livestock has come into particular focus. Cattle release large quantities of methane during their lifetime (a gas that’s more harmful to the planet than carbon dioxide) and it generally takes more resources to produce beef than comparable other food items. However, the scale of the difference between food items – and the emissions associated with meat production compared to other sources of greenhouse gases – vary according to who you read. As this article comparing greenhouse gas emissions from livestock and transport shows, much depends upon whether direct and/or indirect emissions are considered. The use of general figures also masks the fact that agricultural production systems vary widely across the world.

Greenhouse gas emissions associated with UK meat production are significantly lower than the global average. The most comprehensive statistical analysis of global food systems to date (by Poore & Nemecek in the leading academic journal Science), examined emissions, land use, and other impacts of global agriculture using a life cycle assessment. Life cycle figures account for emissions produced along the whole supply chain, including those from land-use change, on-farm activity, feed production, processing, transport, retail and packaging. The results show that beef from UK beef herds had an average emissions intensity of 48.4 kg carbon-dioxide-equivalent per kg retail weight compared to a global average of 99.5 (greenhouse gases are often presented in units of carbon-dioxide-equivalent – this is a common unit of measurement that allows comparisons to be made between emissions of different gases). For beef from UK dairy herds, the figures were 25.9 versus 33.3; for lamb, 37.4 versus 39.7; and for pork, 11.9 versus 12.3.

Data published by the Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board suggest that the average emissions intensity of UK livestock products up to the point they leave the farm gate is even lower. Beef from UK beef and dairy herds had an average emissions intensity of 23.4 kg carbon-dioxide-equivalent per kg carcass weight; lamb 25.2; and pork 4.8. The figure for the most sustainably-reared beef was as low as 5.6 kg carbon-dioxide-equivalent per kg carcass weight.

The over-riding message from these studies is that, if you are going to eat meat, choosing meat from animals that are locally-reared on low-intensively managed farmland is best in terms of reducing the carbon footprint of your diet. Local butchers and farm shops often sell this product and can tell you where the meat originated. If the meat comes from a local farm via a local abattoir, the resulting food miles will be very low. Some of the most sustainable meat production is by local smallholders, many of whom will sell to you directly.

Avoid food waste

Around a third of all food produced each year is wasted – that’s 1.3 billion tonnes of food that’s simply thrown away. Aside from being an incredible waste of money, food waste is a significant contributor to climate change. Any food waste composted or taken to landfill releases methane. Food waste alone generates about 8% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions. In fact, if food waste were a country, it would be the world’s third-largest greenhouse gas emitter.

The Food Savvy website identifies six easy steps you can take to reduce your food waste, save money and help the planet:

The Food Savvy website identifies six easy steps you can take to reduce your food waste, save money and help the planet:

- Plan your meals. Plan your meals for 3-4 days. Check your fridge and cupboards. What’s in stock? What needs eating up? Use a simple meal planner and leave a day blank to mop up unused ingredients and leftovers.

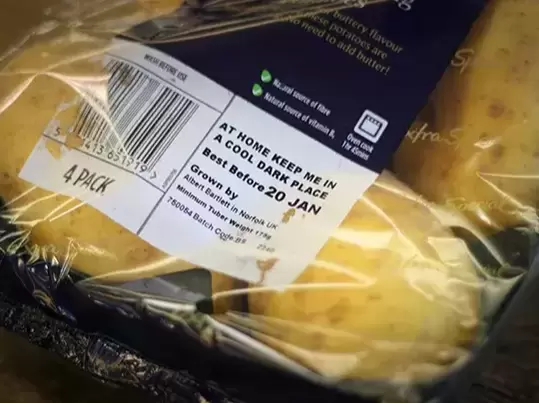

- Shop smart. Always shop with a list. If you are tempted by a bargain, think about whether it can be used, stored or frozen. Check food labels. Buy wonky vegetables. Online shopping is great if you have meal plans that you keep going back to.

- Think about portions. This everyday portion planner from Love Food Hate Waste provides guidance on how much food you need per person, per meal.

- Think about storage. Are you storing food in the right place? Should it go in a cupboard or the fridge? If so, which part of the fridge? Get friendly with your freezer. Freezing acts like a pause button, buying you more time to eat the food you've bought, but don’t forget to label containers and bags.

- Understand date labels. The best before date is about food quality – the food is still good to eat after this date. The use by date is about food safety – eat before or up to the use by date.

- Love leftovers. Don’t throw away leftover food. Cool leftovers as quickly as possible, cover them, refrigerate and use within two days. There are some great websites with recipe ideas to use up leftovers, including BBC Good Food, Food Savvy and Love Food Hate Waste.